The first hurdle, of course, is dealing with another alphabet. However, Hangeul, the Korean alphabet, is actually rather user-friendly. It was developed in the 15th century at the behest of Korea's wise, benevolent, and very favorite king, Sejong. Apparently he thought that the enormous alphabet of Chinese characters (which was the current script at the time) did not suit the Korean language well, and that it was unfair to the common man, as the learning of Chinese characters was something that only upper class people with time to study and access to education could afford to do. To say that Hangeul simplified the character system is a gross understatement. Today, many of the original letters exist only in memory or collect dust in archaic words and forms, so it is even more streamlined.

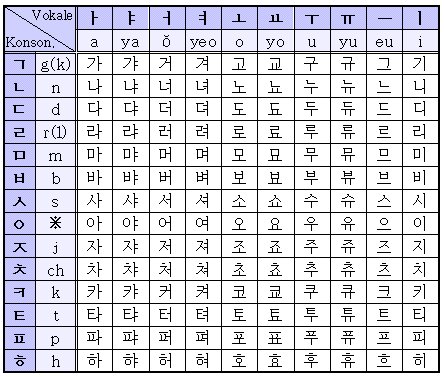

See? Easy!

Hangeul consists of 14 consonants, 5 double consonants, and 21 vowels. What an absurd number of vowels! How can the human mouth even make that many sounds?! Well, I call them vowels for easy reference, in fact Korean vowels include sounds like "ah," and sounds like "yah," and double vowels combined from two symbols, and diphthongs like "way."

Surprisingly, with all these vowel sounds, there are still phonemes for which Korean has no single letter. For all you non-language nerds out there, a phoneme is, in layman's terms, the simplest sound you can make without changing the shape of your mouth, like "f," "sh," or "oo." It is through this discovery that I had a revelation about my own language. Some single vowels in English are in fact not phonemes, but a combination of sounds. The long I in die or the long A in ace, for example, though represented by only one letter, still require your mouth to make two separate sounds. Try it, slow down your speech and you will notice your mouth forming what you thought was one vowel with two distinct vowel sounds. So it is that in Korean, die is not one syllable, but two (다이 = da-ee), and ace is not one but three (에이스 = eh-ee-suh). The third is due to the fact that the "S" sounds becomes a "T" sound on the end of a syllable, so for that reason, among many others, words often get an extra syllable. Korean is also not too fond of consonant clusters, and thus Sprite, which in English has one syllable, has five in Korean (스프라이트 = suh-puh-ra-ee-tuh). By far the most outrageous transliteration I've seen yet.

These quirks aside, the script is in fact remarkable easy to learn. It took me about two days to commit it to memory, although as always noise from one's own alphabet gets in the way when reading a new one. For example, what sound doesㅌ make? Oh, well that's an E of course. Nope, that's a T. What about ㄹ? That's a 2, obviously. Wrong again, that's R/L (incidentally, one of the reasons that Koreans mix these letters up in English so much, they have no cause to differentiate the sounds in their own language). What about ㅇ? Well that has to be an O. Or at least a 0. Nope, that letter is actually silent. Or if it's feeling sly -- and aren't we all when we're at the end of a syllable -- it's NG.

Also, you face the hurdle of dealing with a syllabary. Hangeul has letters, but they don't exist on their own, only in syllables of two or three letters. So words cannot look like

ㅎㅏㄴㄱㅡㄹ, that would of course be silly. It's written 한(Han)글(Geul). Naturally, we English speakers read and understand words one syllable at a time, but we are not used to letters stacked up on one another.

My experience with the language has been good, so far. It's not terribly difficult to pick up basic words and phrases, and once you master the alphabet and some survival vocabulary, ordering food and getting around becomes immensely easier. You might actually know what dish you're pointing at on the menu. My major problem, as someone who spent the last few years studying dead languages, is actually using it. I feel immensely confident reading and writing Korean (within the limits of my grammar and vocabulary abilities), but speaking it and listening to it (something I never had to do with Greek or Latin) are a whole other ballgame. When speaking, the problem of pronunciation of course rears its ugly head, and my feeble attempts at communication usually go over the head of the well-meaning but throughly nonplussed Koreans with whom I interact. The hardest pronunciation problem to deal with is the presence of three very similar sounding vowels, 으 (euh), 어 (uh), and 오 (oh). To use a frame of reference that only my one reader who is a Classicist will understand (Phil, I'm looking at you), this is at least ten times worse than the frustration of first coming to terms with α, ο, and ω.

The worst feeling in the world, as any learner of a foreign language knows, is the false confidence that comes with self-study. When speaking to a Korean, on a very routine basis, I find myself in a magical, miraculous sort of rhythm where all my vocabulary falls neatly into place, my grammar is flawless, and my pronunciation, though not perfect, is bordering on mediocre. I rattle off a whole paragraph and mentally pat myself on the back as I can see understanding register in my interlocutor's eyes. But then, of course, comes their thought: "well, this foreigner's Korean is actually not bad! Good for him," followed by a veritable torrent of rapid-fire foreign language way beyond my capability, and my guilty admission that I haven't understood a word of what they said. Dealing with a living language is a humbling experience, although I get oohs and aahs from my students anytime I tell them that their jacket is blue, so I guess that's something.

One of the most interesting benefits of learning Korean is gaining insight into Korean culture using nothing but language and grammar. You can learn a lot about a people by the way that they write and talk. Korean has seven registers of formality for use when speaking to people of different social stations in different settings. This goes well beyond the difference between "Open the door" and "Would you please open the door?" Depending on to whom you are speaking, you might use the formal polite, the informal polite, the humble, the honorific, and so on. When Koreans first meet someone, they have to ask all sorts of probing questions like "How old are you?" "What do you do?" "Are you married?" and "How much money do you make?" just so they can figure out how to address each other in the rest of the conversation. Luckily, most don't expect foreigners to catch on to this quickly, so one can get away with the formal polite most of the time.

My favorite thing that I've learned so far is that Koreans are the most incredulous people I have ever met. I don't know if they suspect that they are living in a fantasy world, if they naturally distrust everyone, or if they all have problems hearing, but from what I can understand, they are constantaly questioning the legitimacy of everything. Within 2 weeks of coming here, 4 of my only 50 vocabulary words revolved around this, translated as follows:

그래요? - Really?

헐! - What the...?

정말? - REALLY?

진짜? - No, like, are you seriously for real right now?

Admittedly, my vocabulary is limited, but it seems like 80% of the conversations in the office are nothing more than an announcement and a polite but patent disbelief in the statement's veracity. I feel like one could have an entire conversation using nothing but the words above. Why so mistrustful, Koreans?

I'll stop rambling on about language now, as I'm sure most of your eyes glazed over paragraphs ago. But for those of you who don't like language lessons in their blog posts, I apologize, but I will tell you what I tell my students: "Grammar is fun and you should love it because I love it, dammit!"

The worst feeling in the world, as any learner of a foreign language knows, is the false confidence that comes with self-study. When speaking to a Korean, on a very routine basis, I find myself in a magical, miraculous sort of rhythm where all my vocabulary falls neatly into place, my grammar is flawless, and my pronunciation, though not perfect, is bordering on mediocre. I rattle off a whole paragraph and mentally pat myself on the back as I can see understanding register in my interlocutor's eyes. But then, of course, comes their thought: "well, this foreigner's Korean is actually not bad! Good for him," followed by a veritable torrent of rapid-fire foreign language way beyond my capability, and my guilty admission that I haven't understood a word of what they said. Dealing with a living language is a humbling experience, although I get oohs and aahs from my students anytime I tell them that their jacket is blue, so I guess that's something.

One of the most interesting benefits of learning Korean is gaining insight into Korean culture using nothing but language and grammar. You can learn a lot about a people by the way that they write and talk. Korean has seven registers of formality for use when speaking to people of different social stations in different settings. This goes well beyond the difference between "Open the door" and "Would you please open the door?" Depending on to whom you are speaking, you might use the formal polite, the informal polite, the humble, the honorific, and so on. When Koreans first meet someone, they have to ask all sorts of probing questions like "How old are you?" "What do you do?" "Are you married?" and "How much money do you make?" just so they can figure out how to address each other in the rest of the conversation. Luckily, most don't expect foreigners to catch on to this quickly, so one can get away with the formal polite most of the time.

My favorite thing that I've learned so far is that Koreans are the most incredulous people I have ever met. I don't know if they suspect that they are living in a fantasy world, if they naturally distrust everyone, or if they all have problems hearing, but from what I can understand, they are constantaly questioning the legitimacy of everything. Within 2 weeks of coming here, 4 of my only 50 vocabulary words revolved around this, translated as follows:

그래요? - Really?

헐! - What the...?

정말? - REALLY?

진짜? - No, like, are you seriously for real right now?

Admittedly, my vocabulary is limited, but it seems like 80% of the conversations in the office are nothing more than an announcement and a polite but patent disbelief in the statement's veracity. I feel like one could have an entire conversation using nothing but the words above. Why so mistrustful, Koreans?

I'll stop rambling on about language now, as I'm sure most of your eyes glazed over paragraphs ago. But for those of you who don't like language lessons in their blog posts, I apologize, but I will tell you what I tell my students: "Grammar is fun and you should love it because I love it, dammit!"

No comments:

Post a Comment